Telemedicine, Minority Groups, and Decreasing the Maternal Mortality Rate

Last year, we published an article entitled Telemedicine, Rural Pregnancy, and Decreasing the Maternal Mortality Rate. That article cites data from five years ago, which said that for every 100,000 U.S. births, 17 women die from pregnancy complications. Since then, data from 2020 has been published, which shows the ratio has increased by 40%, from 17 to 23.8, a rate three times higher than other high-income countries.

The national average is bad, but when we look closer, we see the maternal mortality risk is not equal across populations. In our previous article, we focused on the rural demographic. Here, we will compare the level of risk between races and ethnicities.

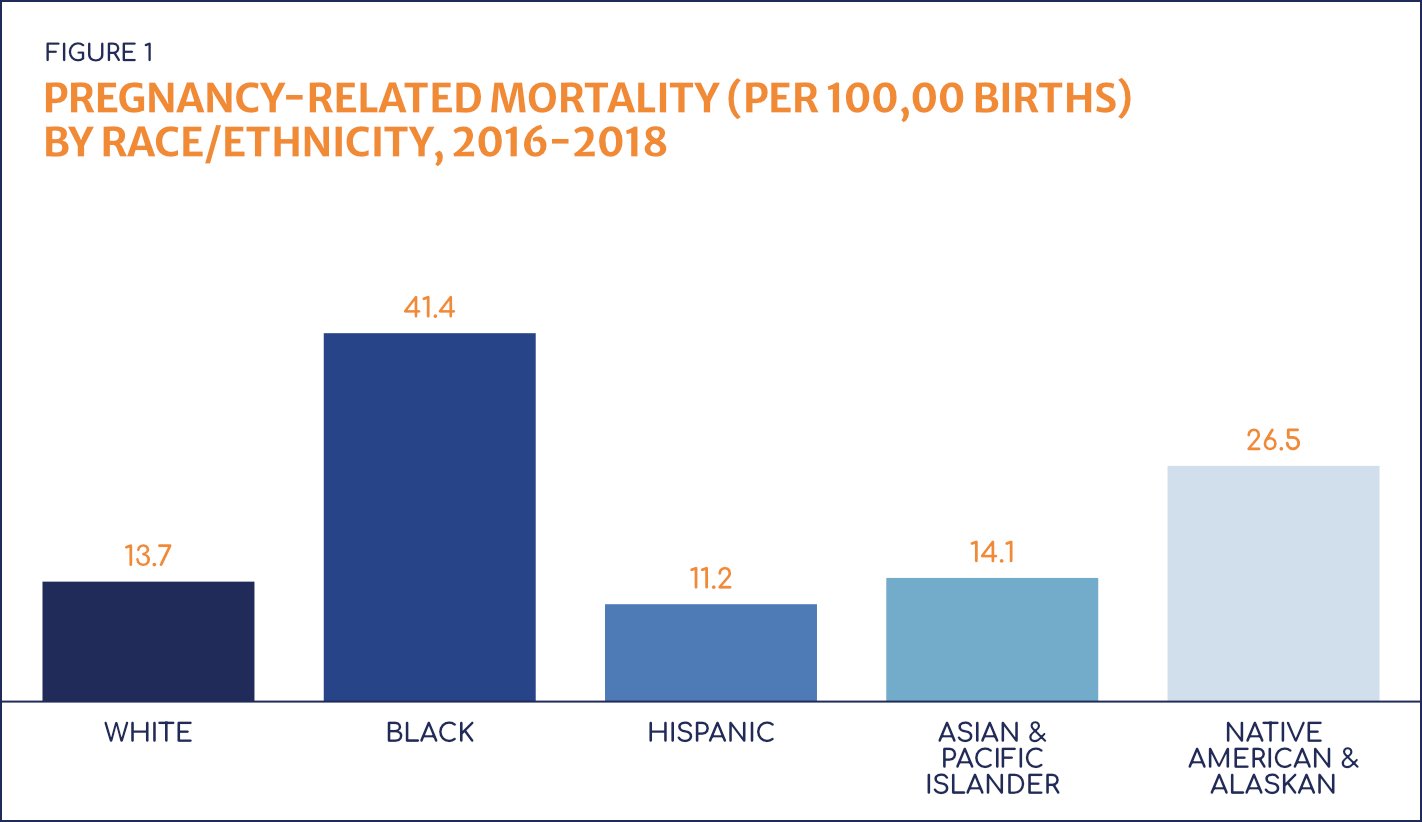

Recent data from the United States Government Accountability Office shows minority women have higher rates of pregnancy-related death than White women (Figure 1) and carry the highest risk for severe maternal morbidity (maternal morbidity refers to conditions that reflect unexpected outcomes of labor and delivery and result in short- or long-term health consequences).

We cannot view these statistics without concluding that inequalities exist in maternal healthcare. But before we discuss solutions, let’s gain a better understanding of the key issues surrounding this problem.

Key Issues

We are not going to deal directly with systemic racism, implicit bias, and social determinants of health (SDOH) in this article, but it is vital to understand these issues and their ties to the challenges that we will discuss. If you are not familiar with these topics, we encourage you to visit the following resources:

Health Affairs: Structural Racism in Historical and Modern US Health Care Policy

The Commonwealth Fund: Reducing Racial Disparities in Health Care by Confronting Racism

March of Dimes: Health Disparities and Pregnancy

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists: Importance of Social Determinants of Health and Cultural Awareness in the Delivery of Reproductive Health Care

Journal of the American Heart Association: Social Determinants of Suboptimal Cardiovascular Health Among Pregnant Women in the United States

1. Timely Care

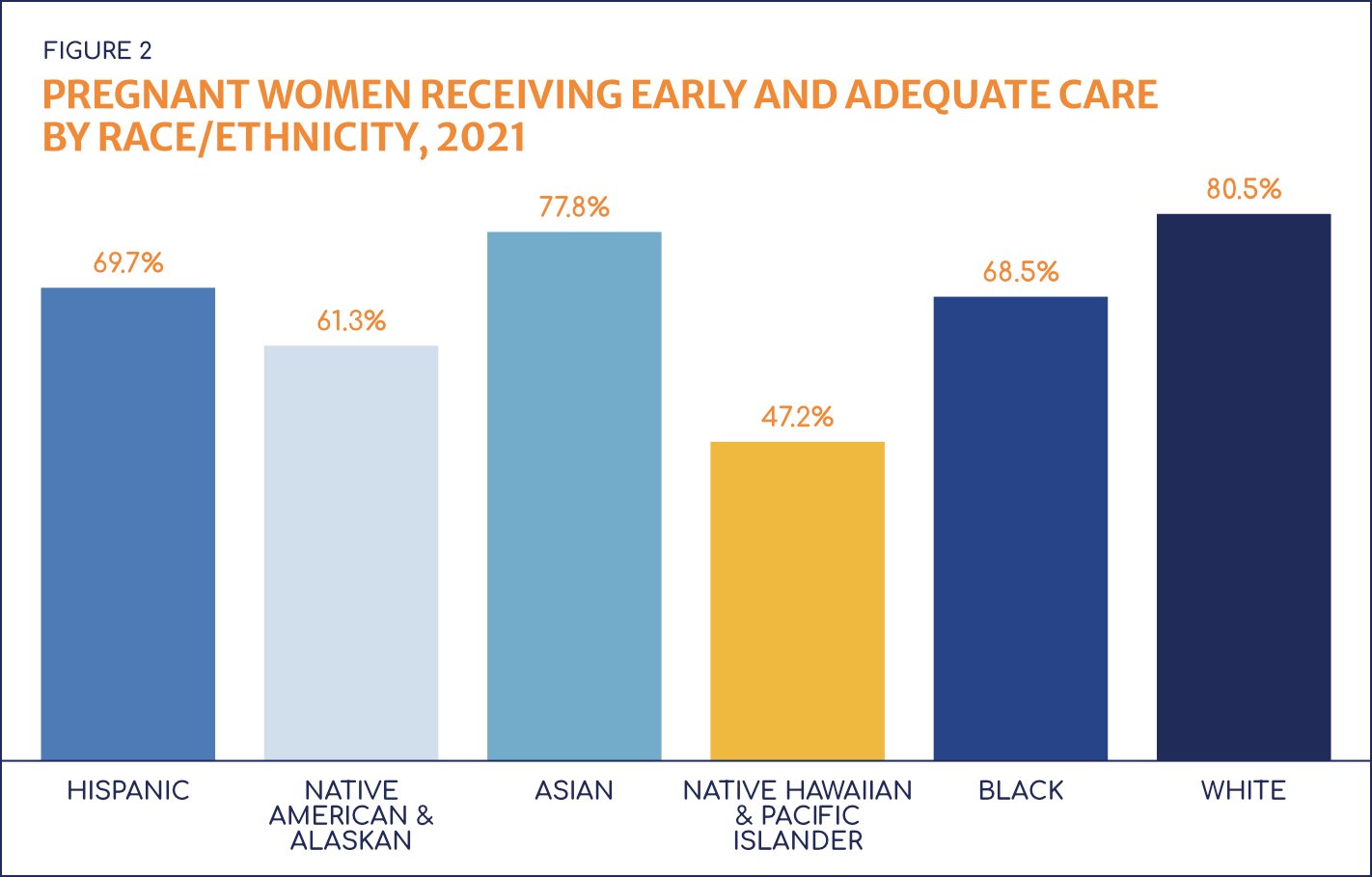

The first problem we’ll tackle in detail is timely care. Adequate prenatal care begins in the first four months of pregnancy and includes the appropriate number of visits for the baby’s gestational age. Timely care is important because research indicates a link between fewer prenatal visits and maternal mortality and morbidity, as well as low birthweights, preterm births, and infant mortalities.

Recent data from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services clearly illustrates racial disparities in access to timely care (Figure 2). We also know results are worse for women who go without prenatal care completely: they are 3-4 times more likely to die from pregnancy-related complications than their peers who do receive care.

2. Quality Care

Even when non-white patients do access timely care, the second problem we need to consider is the quality of care they receive.

We support and appreciate all our nation’s healthcare workers (including our own incredible team), but we must admit that not all hospitals are equal. Research shows women of color suffer more often from a lack of high-quality care. Hospitals with higher percentages of non-white patients tend to have higher mortality rates and lower rates of effective, evidence-based care. They also perform poorly on delivery-related indicators when compared to other facilities.

3. Risk Factors and Likelihood of Complication

Lastly, let’s consider risk factors and the likelihood of complications during pregnancy. A recent study indicates the leading causes of maternal death are obstetric embolism and eclampsia and preeclampsia. (For the clinical folks in our audience, the authors note amniotic fluid embolism, pulmonary embolism, and any other type of embolism occurring during pregnancy or the postpartum period were included in the obstetric embolism category.)

Women with pre-existing conditions like asthma, diabetes, and high blood pressure are at a much higher risk for pregnancy complications, and according to Blue Cross Blue Shield, and are more likely to identify as a minority. One study showed Native American, Native Alaskan, and Black people are 1.5-2 times more likely to have diabetes. The American Heart Association found Black women are twice as likely to have high blood pressure. Additionally, a Black or Hispanic woman who develops pregnancy-induced high blood pressure is six times more likely to die than a White woman.

Review of Telemedicine

Now, let’s turn to the technology we believe can reduce racial disparities and maternal mortalities: telemedicine. Defined simply, telemedicine uses telecommunication technologies to deliver medical, diagnostic, and treatment-related services. Examples include remote monitoring devices, virtual appointments, and remote diagnostics. With its many benefits, and the potential to increase access to care, telemedicine is poised to impact every area of healthcare, including maternal-fetal care.

So, how can telemedicine positively impact the key issues we’ve outlined?

Overcoming Key Issues with Telemedicine

1. Telemedicine and Providing Timely Care

One type of telemedicine, dubbed the hub-and-spokes model, uses technology to connect centrally located experts with remote and underserved areas. This model provides patients with both a local touchpoint and an expert provider. For example, one fetal telecardiology program connected underserved patients with a cardiologist who practiced 243 miles away. When surveyed about their experience, all patients preferred the telecardiology appointments due to saved time and costs.

In a 2012 analysis, which was completed years before telemedicine use skyrocketed, researchers asked low-income, urban-located Black and Hispanic people about their feelings toward telemedicine. Both groups indicated telemedicine provided increased access and reduced wait times compared to non-telemedicine options.

We also have evidence that telemedicine can result in increased efficiency, which increases a clinic’s ability to provide timely care. One clinical location implemented our telesonography® solution, TeleScan®, and was able to provide 20% more patients with an ultrasound appointment. That resulted in a 50% reduction in the time until the next available appointment.

2. Telemedicine and Increasing Quality of Care

By connecting underserved patients with expert care, telemedicine can also improve the quality of care they receive. Increased access to maternal-fetal medicine specialists is associated with improved health outcomes among pregnant patients with chronic illness and complications. In a 2022 study of high-risk obstetric patients (of which 72% were Native American/Alaskan and 23% were Hispanic) 94.7% were satisfied with the quality of service being provided via telemedicine and 71.5% would consider receiving telemedicine care again.

Better outcomes from telemedicine persist outside of obstetrics as well. One systematic review assessed the effectiveness of telehealth and patient satisfaction and found improved outcomes made up 20% of success factors. And 75% of clinicians believe telehealth enables them to provide quality care.

3. Telemedicine and Caring for Risk Factors

Finally, what about the risk factors that minority patients are more likely to experience—conditions like diabetes and high blood pressure?

Diabetes, especially gestational diabetes, has been widely studied. Telemedicine patients reach optimum glycemic control sooner and with fewer insulin doses than those without telemedicine—and experience up to a 66% decrease in both planned and unplanned appointments. A study from the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences found telemedicine also improved the utilization of prenatal care among pregnant women with pre-existing diabetes, more than one-third of whom were Hispanic. Patients experienced fewer inpatient admissions, lower insulin use rates, and lower costs.

Regarding high blood pressure, one study found both clinic-based care and telemedicine care were successful in lowering blood pressure. However, after six months, patients supported by telemedicine were more satisfied with their treatment than clinic-based patients, more likely to rate their care as high quality and convenient, and more likely to take their blood pressure at home.

It’s time for Telemedicine

The data is clear: maternal mortality is a huge problem for our nation, and it disproportionately impacts minority demographics. The good news is, we have the technology to take a big step forward in providing equitable care. The pandemic accelerated our adoption of telemedicine, and legislative efforts are under way to keep it accessible and affordable. That means the time for telemedicine is now.